Wednesday, August 10, 2016

"SPOOKY ACTION AT A DISTANCE" IS IT REALLY SPOOKY?

"Spooky action at a distance", as Einstein called it, refers to the experimental fact that particles can have an effect on each other instantly, even when separated by large distances. For example, if two photons are created collectively in what is called an entangled state and the angular momentum of one is altered, then the angular momentum of the other one will shift in a corresponding fashion at the same time, no matter how far apart the particles are. This "spooky" behavior has been known for almost a hundred years and still is a source of befuddlement.

Still there is a concept in which the end result is not spooky, but rather a natural consequence. I'm referring to Quantum Field Theory, which identifies a world made only of fields, with no particles. What we refer to as a particle is really a chunk, or quantum, of a field. Quanta are not localized like particles, but are spread out across space. For example, photons are parts of the electromagnetic field and protons are pieces of the matter field. These units evolve in a deterministic way as per the basic field equations and there is a term in these equations that limits the speed of propagation to the velocity of light.

However the QFT equations don't tell the whole story. There are events that are not described by the field equations-- for example, when a field quantum transfers energy or momentum to another object. This event is non-local in the sense that the change in, or even disappearance of, the quantum happens immediately, no matter how spread-out the field may be. It can also happen with two knotted quanta-- no matter how much they are separated. In QFT, this is required if each quanta is to act as a unit, as per the fundamental basis of QFT.

There is a major contrast between quantum collapse in QFT and wave-function collapse in QM. The previous is a real physical change in the fields while the following is a change in our knowledge. Although we don't have a theory to describe quantum collapse, there is nothing irregular about it. To quote from Fields of Color: The theory that escaped Einstein:

In QFT the photon is a spread-out field, and the particle-like activity happens because each photon, or quantum of field, is consumed as a unit ... It is a spread-out field quantum, but when it is absorbed by an atom, the entire field vanishes, no matter how spread-out it is, and all its energy is placed into the atom. There is a big "whoosh" and the quantum is gone, like an elephant disappearing from a magician's theater.

Quantum collapse is not an easy concept to accept-- perhaps more difficult than the concept of a field. Here I have been working hard, trying to convince you that fields are a real property of space-- indeed, the only truth-- and now I am seeking you to accept that a quantum of field, spread out as it may be, quickly disappears into a tiny absorbing atom. Yet it is a process that can be visualized without inconsistency. In fact, if a quantum is an entity that lives and dies as a unit, which is the very meaning of quantized fields, then quantum collapse must take place. A quantum can not separate and put half its energy in one place and half in another; that would violate the fundamental quantum principle. While QFT does not provide a reason for when or why collapse occurs, some day we may have a theory that does. In any case, quantum collapse is vital and has been demonstrated experimentally.

Some physicists, including Einstein, have been bothered by the non-locality of quantum collapse, claiming that it violates an essential postulate of Relativity: that nothing can be sent out quicker than the speed of light. Now Einstein's postulate (which we must keep in mind was only a guess) is without a doubt valid in relation to the evolution and propagation of fields as explained by the field equations. However quantum collapse is not described by the field equations, so there is no reason to assume or to insist that it falls in the domain of Einstein's postulate.

Read more here.

Tuesday, August 2, 2016

Dear New York Times

In the article ("With faint chirp, scientists prove Einstein correct", p. A1, 2/12/16) we study that black holes were part of Einstein's theory. The reality is considerably contrary. "Einstein argued vigorously against black holes [as] incompatible with reality" (see "Black Holes" by R. Anderson) and his rivals held back their acceptance for many years.

Einstein was also wrong when he denied Quantum Field Theory. According to his biographer A. Pais," QFT was repugnant to him". This is contradictory because QFT, and only QFT, reveals and resolves the paradoxes of Relativity and Quantum Mechanics that most people struggle with (see "Fields of Color: The theory that escaped Einstein" by this writer).

Perhaps the biggest irony is the statement, "according to Einstein's theory, gravity is caused by objects warping space and time". Although that is what everybody thinks today, the reality is that Einstein recognized gravity as a force field, similar to electromagnetic fields, but that it is created by mass, not charge. That an oscillating mass creates gravitational waves is no more mysterious or unexpected than that electromagnetic waves are generated when electrons move back and forth in an antenna. To Einstein, curvature was a secondary result, similar to the changes in space and time generated by motion according to his Special theory of Relativity.

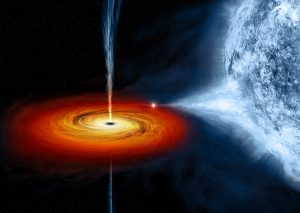

Black holes. Contrary to numerous reports, black holes were actually not part of Einstein's concept. In fact Einstein argued vigorously against black holes [as] incompatible with reality, and his opposition held back their approval for many years.

Summary. Gravitational waves are easy to understand if you recognize gravity as a force field, similar to the electromagnetic field (QFT). And while the contraction effect is far more subtle, it is not that much different from the F-L contraction that has been accepted for over a hundred years.

Learn more here...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)